The Anatomy of Chess Solving—Episode 01

The problemist's art has always been a bit of a mystery to chess players. Are chess problems merely puzzles with unique and rather curious solutions, or is there something more to them? Join Satanick Mukhuty, our Chess Composition Editor, as he dissects the art of chess problem-solving in his new blog, The Anatomy of Chess Solving. The inaugural episode showcases six meticulously curated problems designed to illuminate the subtle nuances and clever craftsmanship of problem chess. To get the most out of this article, take 10 minutes to study each position before reading the explanatory text. This will help you develop your problem-solving skills and appreciate the artistry behind each chess composition.

Chess Problem Basics: Getting Started

In mainstream chess discourse, the terms 'chess problem' and 'chess puzzle' are often used interchangeably to refer to chess positions where one has to uncover the best move or a sequence of moves leading to a definite outcome. However, in a strictly technical sense, there is a fundamental difference between the two. A problem is constructed from scratch by a composer to illustrate a striking idea or theme. Its design adheres to certain artistic principles. On the other hand, puzzle is a more relaxed term that may describe a chess composition but typically refers to tactics derived from actual games. Sure, a problem has a puzzle element. Outwardly, it presents a position to be solved, such as 'White to play and mate in 2.' On a deeper level, however, it is a work of art that aims to showcase a novel theme in the most elegant way possible. Thus, problems are more than just training exercises for players to enhance their skills. They represent a distinct aspect of chess culture, with literature and history of their own, independent of the practical game. And this is what we aim to explore in the present blog.

Let's get hands-on: I could keep writing about chess problems – what they are and are not – but examples speak louder than words, and our first one, a two-move directmate or a two-mover, should give you a pretty good idea of what a chess problem theme is like.

A directmate is a problem where White plays first and aims to checkmate Black in a specified number of moves against any defence. The terminology is straightforward: a two-move directmate is called a two-mover, a three-move directmate is a three-mover, and any directmate requiring more than three moves is called a more-mover. In the current article, we will focus on two-movers, laying the groundwork for future discussions on three- and more-movers.

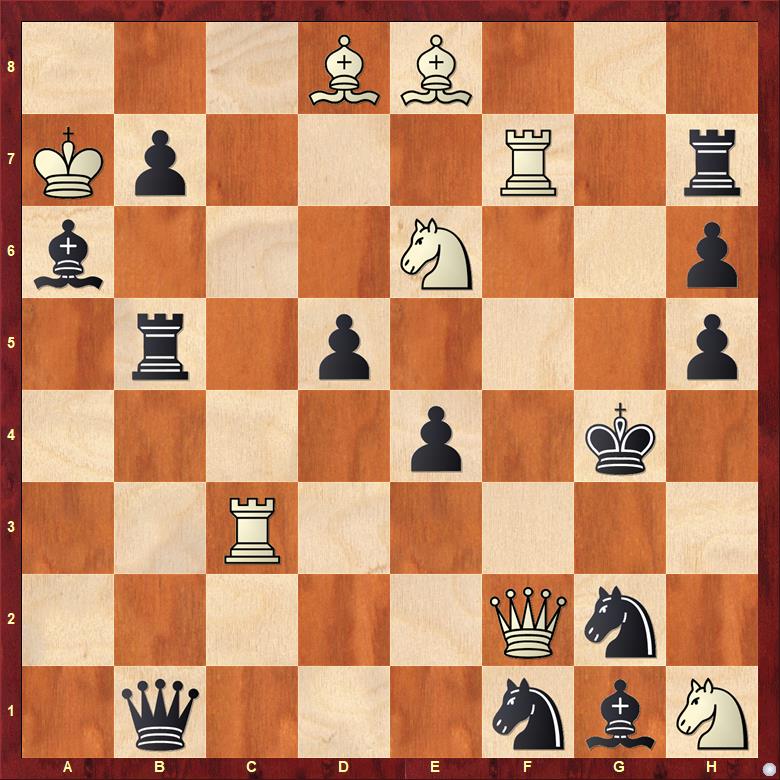

1.

Lev Loshinsky, Chyrvonaya Belarus 1932, 1st Prize

Where do we start with a problem like this? The diagram has 21 units, which can seem overwhelming at first! But hold on, even in this chaos, we have a clear target: the black king. We have to mate it in the quickest possible way. And good for us, swarmed by white pieces, it is already in a mating net. The black king has no escape squares. In such a scenario, the trick often is to threaten a mate in one move. With which piece can we do so? It is logical to use the most underutilised unit, the piece most remotely located from the enemy monarch. In this case, it is clearly the bishop on e8, which is begging to be put on the c8-h3 diagonal!

1.Bd7 directly, threatening discovered check and mate by moving the e6 knight on the next move, fails to 1...Rxf7. Therefore, the key should be 1.Ng7!, threatening 2.Bd7# instead and, at the same time, disallowing Rxf7. The symbol "!" implies that this is the only move that solves the problem. Now, Black has multiple ways to parry the said threat, called defences. But each of these enables White to mate differently. For instance, 1...Ng3 allows 2.Rxg3#. Similarly, 1...Nh4 (Nf4) and 1...Bxf2+ are met with 2.R(x)f4# and 2.Nxf2#, respectively. These two-move sequences constitute what is known as the variations of the solution. The main variations here are 1...Nfe3 2.Qg3#, 1...Nge3 2.Qh4#, 1...e3 2.Qf3#, 1...Rb6 2.Qf5#, and 1...d4 2.Qe2#. Although Black manages to prevent 2.Bd7#, each move frees Qf2 from its pin by cutting off the a7-g1 diagonal. This repeated unpinning of the queen, showcased in no fewer than five distinct variations, is the overriding theme of the problem.

Thus, a theme may be defined as a recurring tactic or geometric pattern that weaves together multiple variations, providing a unifying thread throughout the composition. Another instructive case is presented next.

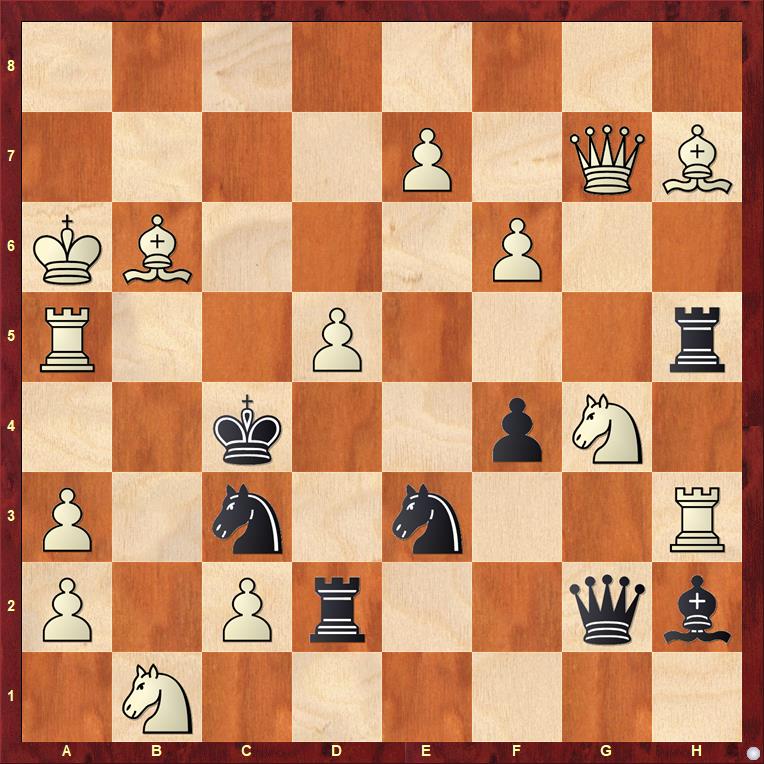

2.

Alfred Olaf Karlstrøm, Arbejder-Skak 1934, Prize

As in the previous problem, the black monarch is again trapped in a mating net, devoid of any flight squares. Let's begin our investigation by taking stock of the different roles the white units play in the diagram. The two bishops, the knight on b1, and the rook on a5 are all aimed at squares in the enemy king's immediate vicinity. The h3 rook, too, x-rays the c3 square, while the g4 knight is also poised to join the fray. By far, White's queen is the most detached piece from the bK. The key, therefore, must be with the queen. It needs relocating to a better square.

The solution starts with 1.Qg8!, threatening 2.Qc8#. If Black guards c8 by playing 1...Qxg4, White responds with 2.Nxd2#. And moving the c3 knight randomly, say 1...Ne4/Nb5/Na4, runs into 2.R(x)a4#. But the thematic variations arise when Black captures on d5: 1...Qxd5 2.Nxd2#, 1...Rdxd5 2.Bd3#, 1...Rhxd5 2.Ne5#, 1...Ncxd5 2.Ra4#, and 1...Nexd5 2.Rxc3#. The black pieces consecutively get pinned on d5, allowing White various pin-mates. And this precise setup is made possible by placing the queen specifically on g8, rather than on any other square on the eighth rank!

This second problem can be seen as a fascinating antithesis to the first. Loshinky's composition features the unpinning of a white queen in five variations, whereas Karlstrøm's creation showcases consecutive pieces getting pinned by a white queen in five variations! A strong solver develops a 'problem instinct,' sensing these subtle patterns and motifs that underlie the position, even before they have found the key move. So, getting a handle on problem themes does double duty: it makes you appreciate the artistry better and helps you solve more efficiently.

A Note About Key Moves

When solving chess puzzles (i.e., tactics), we have all been taught to start by looking at checks and captures. However, in composed problems (especially of short length), the solution typically doesn't begin with a check. Occasionally, the first move may be a pawn capture, but the capture of a piece is also super-rare. Why is this the case? Well, in an adversarial problem, more than anything else, what the composer aims to depict is the element of contest between the two sides. An ideal directmate, therefore, would be the one that leaves as many resources as possible to the defending side after the key. A check is too brutal for that and drastically reduces the number of options, and the same goes for a capture that removes a whole piece from the board. However, long more-movers, where the post-key play is sufficiently elaborate, often do start with checks. But even there, a composer will prefer a quiet, subtle key instead of a check if they can. Needless to say, a good key must not be obvious. And a well-hidden key move is even better if it seems illogical. The best keys appear to weaken White's position and increase Black's possibilities. The following example provides a striking illustration.

3.

Jorge Marcelo Kapros, Problem Observer 1997, 1st Prize

We have seen how pinpointing the least optimal piece on the board and finding a way to mobilise it can be a powerful strategy, streamlining our search for candidate moves. In some instances, however, it helps to be more imaginative and expect the unexpected. This problem is a case in point. The stunning key here is 1.Nc4!, sacrificing the knight on a square where it can be taken in no less than five ways. Given the threat 2.Nb2#, Black has to capture on c4, and the five captures lead to five different mates: 1...Kxc4 2.Qb5#, 1...Nxc4 2.Qxb3#, 1...Rxc4 2.Qh7#, 1...Bxc4 2.Qb1#, and 1...dxc4 2.Qe4#. The last three variations in particular involve self-block. By occupying c4, Black inadvertently blocks their king's escape route, enabling White to mate.

Here, too, an experienced solver's attention will instinctively be drawn to the c4 square, remarkably guarded by five of Black's six pieces. 1.Nc4 will be their natural first choice, with the remaining task being merely to confirm that it indeed works in all variations.

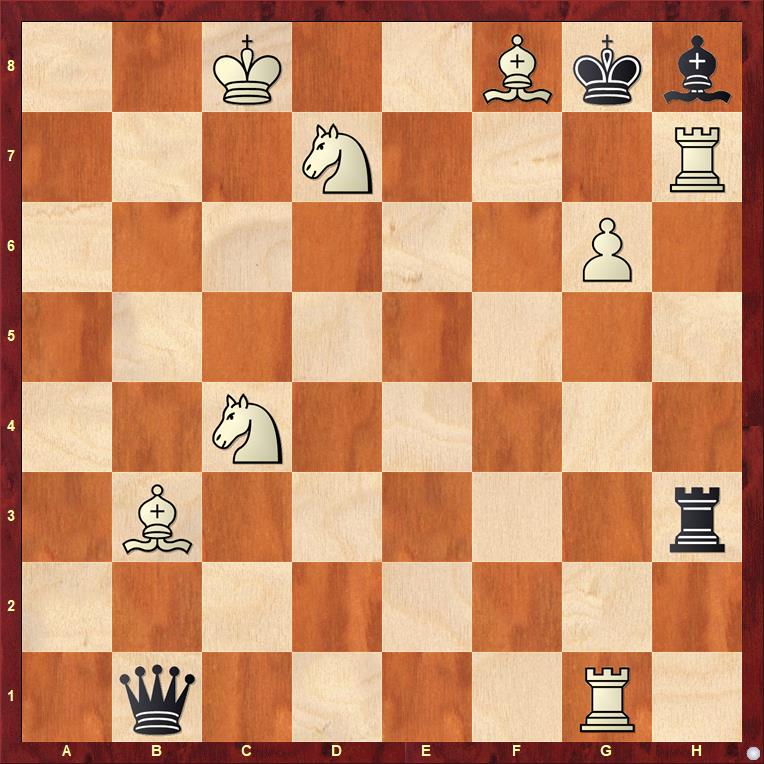

4.

Joe Bunting, To Alain C. White, 1945

One of the surprising aspects of 1.Nc4 in the previous problem is that it provides the black king with a flight square, a luxury it didn't have in the starting diagram. This type of 'flight-giving' key is particularly prized in chess composition, whereas a key that takes away flight without giving one is frowned upon. Problem 4 presents an extraordinary case: the key move grants the black king, initially with zero escape squares, as many as three flights! The solution begins with the uncanny 1.Qf6!, which, though threatening 2.Qxf5#, surprisingly leaves three squares in the black monarch's immediate vicinity undefended. However, as the following variations show, White's strategy hinges on the fact that occupying any of these squares would pin a black piece, allowing White a pin-mate: 1...Kd5 2.Qe6#, 1...Kd3 2.Qd4#, and 1...Kf4 2.Rxg4#. And of course, any move of the f5 bishop, say 1...Bg6, runs into 2.Bc2#, while 1...Nd4 is met with 2.Qxd4#. Pretty!

5.

Adriano Chicco, Probleemblad 1950, 1st Prize

This problem and the next involve battery-play. In chess composition, a battery refers to a specific arrangement of two pieces, lined up on the same rank, file, or diagonal, positioned to deliver a discovered check when the front piece moves out of the way. In the diagram above, the b3 bishop and the c4 knight form a battery. However, moving the knight on c4 immediately to deliver check is ineffective, as long as the b3 bishop is tied down by both Black's queen and rook. Here again, we have a first-rate flight-giving key: 1.g7!, which threatens 2.gxh8=Q/R#. Two noteworthy variations are 1...Qxh7 2.Ne3# and 1...Rxh7 2.Nb2#. As Black's queen or rook captures on h7, White moves the c4 knight to block the other piece, delivering mate with the bishop behind! 1...Kf7 2.Nd6#, 1...Kxh7 2.g8=Q#, and 1...Bxg7 2.Rgxg7# are the remaining variations.

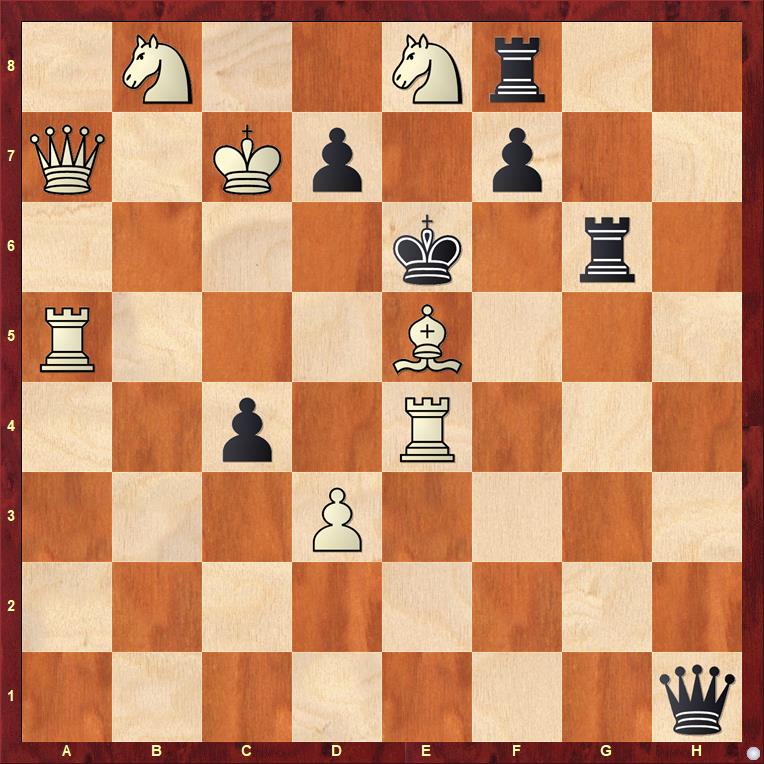

6.

C.G.S. Narayanan, Northwest Chess 1976, 1st Prize

Narayanan, one of India's preeminent composers, delivers a remarkable key in this early masterpiece.

The rook-bishop battery aimed squarely at the enemy king should immediately catch the solver's attention. However, with Black's queen trained on the e4 rook, there is no use firing it immediately.

The astonishing key is 1.Kb6!. This paradoxically exposes the white king to a flurry of checks, but White counters each one by interposing the e5 bishop on the check line, which simultaneously unleashes the e4 rook, mating the black king – a classic example of the cross-check theme: 1...Qb1+ 2.Bb2#, 1...Qg1+ 2.Bd4#, 1...Kf5+ 2.Bd6#, and 1...Ke7+ 2.Bf6#. And of course, any other black move runs into 2.Qxd7#, which is precisely the threat the key move creates.

Having gone through the examples above, you now likely have a basic sense of chess problems. But you might still wonder: Will solving these positions make me a better player? Well, it will certainly make you a better solver – and isn't that reward enough in itself? In fact, solvers have a competitive landscape all their own, complete with ratings, titles, and tournaments! There are also World Champions in chess solving. The most recent one is the Polish phenom Kacper Piorun.

To chess players new to problem chess, I am sure the setups above would look bizarre or unnatural. But that is because they operate on principles distinct from the ones that govern practical play. However, it should be mentioned that all these positions are legal. That is, theoretically, it is possible to arrive at them from the initial game array through a legal sequence of moves. Furthermore, it's worth noting that these positions are carefully crafted with economy of force in mind, ensuring every unit serves a specific purpose. The board is stripped of unnecessary material, and each piece or pawn must either actively contribute to the solution or prevent unintended alternatives, known as cooks. The stronger the theme, the better the problem – and achieving it with minimal force makes it even more impressive!

Your thoughts, feedback, and comments on this article are welcome! Please feel free to email the author at chessbaseindiasocial@gmail.com.